Where Did Commerce Group Get the Money?

- Details

-

Published: Friday, 17 August 2012 13:58

Where Did Commerce Group Get the Money?

Versión en Español

The last anyone had heard was that the Milwaukee based mining company Commerce Group was struggling to come up with the $150,000 to pay for the appeal proceedings in their case against the Salvadoran government. As July 19th, the payment deadline established by the tribunal hearing the case, drew closer and there was still no news of Commerce Group’s payment, it seemed that the case was all but over.

However, much to the surprise of those following the case, Commerce Group managed to scrape together the cash and paid the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) on the day of the payment deadline, according to government officials in El Salvador. Four days later the ICSID announced that the case would resume.

The question then becomes where did the Commerce Group get the money to continue?

In November of 2011 the company sent a letter to the ICSID claiming they were unable to pay the relatively small fee and even had the nerve to ask that ICSID force the Salvadoran Government to pay for almost $70,000 of their costs, claiming the Government owed them money from overpaid taxes and a security deposit on rented property. The company has not reported any income since the year 2002 and has been scaling down their operating cost over the years, presumably as their finances dwindle. Therefore, if the company really is in the dire straits that they claim and their finances seem to indicate, where did the last minute bail-out come from?

The Commerce Group began their suit against the Salvadoran Government in 2009, demanding $100 million in compensation from Salvadoran taxpayers. Even though there is ample scientific proof, including a recent study by the Ministry of the Environment showing cyanide and iron contamination in the local water, Commerce Group claims that the Salvadoran government is violating their rights as investors by denying them their permits. This case has drawn international attention as an example of the dangers of investor-state clauses in free trade agreements and the Midwest Coalition against Lethal Mining called the lawsuit “a cynical attempt by an unsuccessful company to exploit international trade agreements to make money which they have been unable to make by legitimate means.”

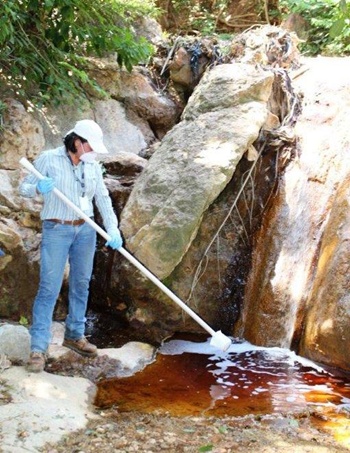

A Recent Photo of the Abandoned CG Mine Site

The MARN Confirms the presence of cyanide and iron in the San Sebastian River, La Unión

- Details

-

Published: Monday, 16 July 2012 18:00

The MARN confirms the presence of cyanide and iron in the San Sebastian River, La Unión

This weekend the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) confirmed the presence of unhealthy levels of cyanide and iron in the San Sebastian River, proposed mining site of the Milwaukee-based company the Commerce Group.

Below is a translation of the updates posted on the MARN website.

Here is the link to the MARN website.

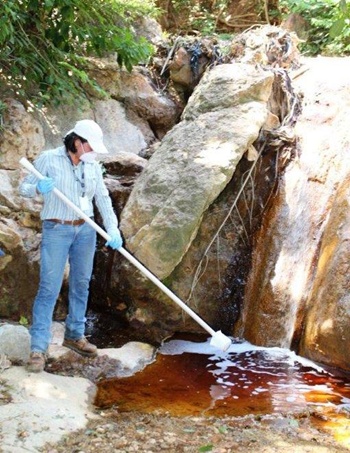

Here are pictures of the pollution in the San Sebastian River.

La Unión, July 14, 2012.

The results of water samples taken by the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (MARN), which were collected two thousand five hundred meters from the bed of the San Sebastian River, in the area of the hamlet of El Comercio in Santa Rosa de Lima, confirmed the presence of cyanide and iron, among other substances.

The main source of contamination that was identified is a discharge of acid water that is rust colored following down from the higher ground on the Cosiguina mountain, an area where industrial mining was in operation for a number of decades.

The samples taken from various stretches of the river indicate that the contamination diminishes in concentration due to the increased water levels from the river during the rainy season. The MARN will carry out a similar study in the dry season to compare the impacts on this body of water.

There are a number of groups of individuals in the area who are mining on an artisanal scale, but it was ruled out that the quantities of cyanide and iron found in the runoff are related to these current practices.

At the petition of the Research of Investment and Trade Center (CEICOM), who associates the numerous causes of death in the locals of Santa Rosa de Lima with causes related to mining, the Vice-Minister of Environment and Natural Resources, Lina Pohl visited the hamlet of El Comercio this morning to see firsthand the investigations that the MARN was doing at the river.

The highest reading of cyanide found in the water flow was 0.450 milligrams per liter. The Salvadoran Compulsory Standard for Water for Human Consumption establishes a maximum limit of 0.05 milligrams per liter, which means that the quantities detected are nine times that amount.

Cyanide is a highly toxic substance for human beings and limits the development of aquatic life. This substance was used in the past in the mining process.

Another finding was high concentrations of iron. The highest reading of iron found was 393.4 milligrams per liter. For this substance, the Salvadoran Compulsory Standard for Water for Human Consumption establishes a maximum of 0.3 milligrams per liter. This means that the levels are over one thousand times the allowed limit.

During the last visit, MARN specialists, with the support of the Firefighters, opened two metallic containers that were left on private property used by the mining company.

In those containers 23 barrels and an un-determined number of bags with chemical substances, which were identified as sodium cyanide and ferrous sulfate, were found. Both of which are chemicals used in the gold extraction process. At this time, the stored materials do not represent a danger, even though they have potential for future danger.

After the tour of the mining area and visits to a number of points where springs of contaminated water begin their flow into the San Sebastian River further downstream, the Vice-Minister said “is is a very complex situation. We are finding a complicated relationship and history between the population and the exploitation of mining resources. This requires a comprehensive social-environmental vision.”

Vice-Minister Pohl stated that they will continue with the investigations of the pollution in the San Sebastian River and in establishing mitigation measures for the impacts caused in this body of water.

LPG: Investigations into pollution in the San Sebastian River

- Details

-

Published: Thursday, 05 July 2012 11:54

Investigations into pollution in the San Sebastian River (LPG)

Yesterday a delegation of specialists collected samples from the river

Written by Ángela Alfaro

Tuesday, July 3, 2012 00:00

Translated by Jan Morrill

Original Version in Spanish

Specialists from the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) took water samples from the San Sebastian River, in Santa Rosa de Lima, contaminated by heavy metals, apparently, the product of substances used during mining activities that were carried out in the area.

The samples were taken within a perimeter of 2.5 km from the river, in the area called El Comercio.

The copper colored water samples will be analyzed in a MARN laboratory, said Roberto Avelar, from the Office of Environmental Compliance of that government agency.

The copper colored stream of water flows from one of the tunnels dug into the high part of the mountain, but the origin of the water has not been determined, explained Avelar.

Locals say that they are used to seeing the water that color, but that they don’t use it for bathing, nor for cleaning their homes, except during the rainy season when the water level rises.

The trip was accompanied by staff from the Firefighters, the National Civilian Police and the Ministry of Health.

Samples Taken

During the visit, specialists from the Firefighters opened two metallic containers that were stored on private property, by a gold mining company that operated in the area and which stopped mining because it permits has been revoked.

In one of the containers that the Firefighters opened 23 barrels of ground powder were found that are presumed to be sodium cyanide. The second container had black bags of ferrous sulfate.

Both are chemicals used in the gold extraction process.

The person in charge of the storage area, who asked to remain anonymous, said that both containers had been there since 2009.

At first glance the chemicals hadn’t had any contact with the ground, due to the fact that they were protected by locks and surrounded by a perimeter wall.

These samples will also be analyzed by the Ministry of the Environment to determine if there was pollution.

Mining

Since the end of last year the Municipal Mayor’s Office of Santa Rosa de Lima has been reporting mining, operations for which they suspect heavy machinery and explosives were used.

In November the Environmental Committee from this community forced the suspension of artisanal gold excavation.

A phone call tipped-off authorities that an “unknown substance” was polluting the Santa Rosa River, in the town of San Sebastian.

At that time the community reiterated that the miners didn’t have authorization to use machines or explosives to extract gold from the San Sebastian mines.

The authorities themselves confirmed that at that moment they didn’t take water samples nor did they inspect to see if there were animals that had died from the pollution.

The Investment and Trade Research Center (CEICOM, in Spanish) asked last April that the government ban any type of mineral exploitation in the country, due to the high levels of heavy metals found in the soil.

The request was accompanied by the results of studies done of the soil in the mining regions, where CEICOM found high levels of heavy metals. Among the findings is the presence of substances like radioactive gases, sulfuric acid, cyanide and mercury, in toxic levels for public health.

Investigations into Pollution in the San Sebastian River

- Details

-

Published: Thursday, 05 July 2012 11:35

Investigations into Pollution in the San Sebastian River

The containers analyzed by MARN presumably contain cyanide and ferrous sulfate

By Gloria Morán

Translation by Jan Morrill

Original Version in Spanish

SAN SALVADOR – The color of the water seems to get worse as the current advances, beginning as an almost clear color until it becomes a strong brown color, which smells of rust and where the rocks which are immersed in the water also seem to have changed color over time. This is the reality for the San Sebastian River in La Union.

Pollution of rivers in El Salvador is well known, but this river in particular has caught the attention of environmental activists and, now, the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) because of the heavy metal contamination supposedly coming from the top of the San Sebastian Mountain, which used to be the site of mining operated by the multinational corporation Commerce Group since 1968.

However, according to a report presented by researcher Flaviano Bianchini, mining operations by other companies date back as far as 1904.

On the edge of the river there are a number of houses. Living there would be a pleasant experience if the pollution from the river weren’t such a dangerous contrast.

Also, close by one can find livestock animals, such as cows, chickens and pigs, all of which consume water from the river. The pigs freely bathe themselves in river water.

Some locals wash their clothes, their cooking utensils and drink water from this river, especially in the rainy season when the current hides the brown color of the water. They think, “if the water is clear, there is no pollution.”

The river accumulates all the acid mine drainage, especially the drainage washed down in the rainy season of metals leaching from the mountain, exactly where the mine was operating.

The Investigation

The MARN began its investigations after receiving complaints from the population which was concerned about the presence of containers holding high risk chemical substances near the top of the mountain.

There were two yellow containers, apparently new, that are secured by two locks on each container and around the containers there was a small brick wall. In one of the containers there were 23 barrels, presumably full of sodium cyanide and the other held black bags of ferrous sulfate, both of which are chemicals used in the gold extraction process.

The MARN took samples of both the chemicals found in the containers as well as the river water, within a perimeter of exactly 2.5 km of the San Sebastian River. The containers were open by staff from the Firefighters of La Union.

In spite of appearance that containers and even the locks had recently arrived, the person in charge of the site, who asked not to be identified, said that they have been there since 2009 and that they are the property of the Commerce Group, a company that brought them to the site with the hope of using them if the Government issued their permits to mine.

Roberto Avelar from the Office of Environmental Compliance of the MARN said he was not sure of the date when they will finish the investigation, but stated that when it’s over they will determine what to do with containers, what measures they will take regarding the river’s pollution and how to protect the lives of the locals.

Artisanal Mining

There is a narrow but long, humid and dark tunnel that is held up by small wooden beams. Young men who live in the town of San Sebastian work in this tunnel. There is not just one tunnel, but five more have also been counted.

Any human who enters in this tunnel and is not prepared for the humidity, the darkness and the lack of air won’t last five minutes before running in search of the exit.

One of the young men who work here said that the workers go in four or five times a day to bring out rock or soil that is then cleaned in an artisanal process to extract the gold. They are called “güiriceros” (which means a foragers).

Their tools are pickaxes, shovels, gas or battery operated lamps, a wheelbarrow, and the willingness to do a dangerous job without adequate safety measures.

There are four young men who aren’t more than 22 years old but no younger than 15 who work in this tunnel. Laughing and joking they said they are used to going in and out of the tunnel and that “we’re used to it.” They are aware of the danger but are not worried about it, this is their job, and that is how they survive.

The Procedure

In 2011 ContraPunto had the opportunity to witness the artisanal process for cleaning rock extracted for mining, and on that occasion a worker, who asked not to be identified, stated that buying soil and finding gold is like playing the lottery, because there are times when the process pays off and times when it doesn’t. He explained that there have been times when he has gone two years without finding any gold.

When the rock is given to workers who process the soil they go through the labor-intensive task of first pulverizing the dirt, which then is called clods. Then it is molded into balls the size of a baseball and which are put in the sun to dry.

The dirt is crushed in an artisanal grinder that is operated by a young man who spends more than five hours moving a double ended stick, that is “v” shaped allowing him to hold on to it, in circles. The lower part of the stick has a ball of cement attached that weighs about 150 pounds. This tool has a deep base where the soil is placed and this is how the work of pulverizing the soil begins.

When the balls of soil are dry, they are put in an oven where some chemicals in the soil are burned off. According to the worker who does the processing, this is to improve the clods and find more gold.

After the oven, the balls are placed again in the grinder where they are mixed with water and mercury, the chemical that separates the gold from other elements. “Even though the mercury leaves the gold white, once it is put in the oven it takes on a lovely color because it is pure 24 karat gold,” said the worker.

He also stated that artisanal mining incurs less risk than industrial mining, because even though the workers have a safety protocol, the toxic emissions from the chemicals they use are much stronger and more dangerous because they work at greater depths within the mountain, apparently around 400 meters deep.

The artisanal mining that is currently operating in the area would still entail risks, but to a lesser degree, due to the fact that this activity does not use chemicals, like cyanide, and would not cause large scale pollution of the environment nor humans.